About the design of the European Union

This post is archived. Opinions expressed herein may no longer represent my current views. Links, images and other media might not work as intended. Information may be out of date. For further questions contact me.

To bring together and hopefully consolidate some of the main arguments I have propounded over an extended series of articles, I here examine the Union’s rule-forming-rule-making architecture.

Given the scope of the topic, this analysis does not cover the institutions of the European Central Bank and the Court of Justice of the EU, not so because they may not have an impact on policy but only due to their function as the monetary and the judiciary respectively.

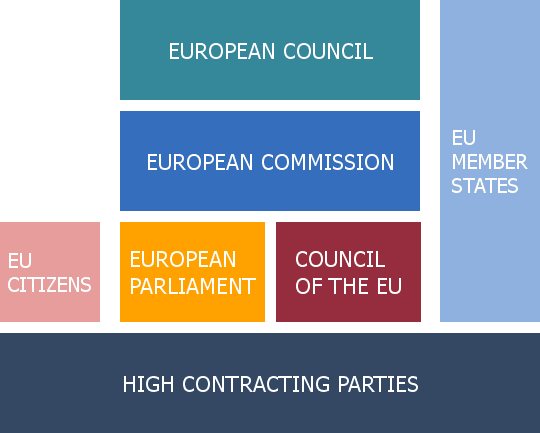

Though I would rather rely only on words and conceptual analysis, I have created a simple illustration that may help guide our thinking:

The lack of artistic elegance notwithstanding, this is supposed to be a representation of the general structure of the EU. It resembles an edifice, with the lower part being the foundation, the side parts are the columns that hold together the middle levels, which are the locus of day-to-day European affairs.

The Union as an inter-state formation

Starting from the basis, the European Union is not an independent state. It is an inter-state organisation founded on international treaties. The contracting parties of those treaties are the Union’s Member States.

Article 1 of the Treaty on European Union reads thus:

By this Treaty, the HIGH CONTRACTING PARTIES establish among themselves a EUROPEAN UNION, hereinafter called “the Union”, on which the Member States confer competences to attain objectives they have in common.

This Treaty marks a new stage in the process of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as openly as possible and as closely as possible to the citizen.

The Union shall be founded on the present Treaty and on the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as “the Treaties”). Those two Treaties shall have the same legal value. The Union shall replace and succeed the European Community.

What we learn from Ar. 1 TEU is the following:

- Member States, not some European Demos, are the constitutional subject of the Union; meaning that the Union rests on a legal order that is supra-national yet contingent on the collective will of the nation states it encompasses (an extra corpus of law, not an independent one);

- the Union’s raison d’être is to promote objectives that are common to the Member States; which reflects the general tendency to “depoliticise” the European level, to make it as technocratic or automatic-rules-based as possible, and to realise a view of the European sphere as primarily that of “common rules without common politics”;

- the telos of the EU is “ever closer union”, which means that there is an inherent preference for integration as such; integration without any specific qualitative characteristic or normative value attached to it;

- the primary law of the Union is not a constitution that could change through ordinary democratic procedures, but a set of inter-state treaties, international covenants, that decisively hamper any effort to make the EU function as a genuine, constitution-based, federal republic.

[see: Europe’s ever closer inter-governmentalism]

The very nature of the EU as an inter-state formation implies the following:

- the supranational stratum does not have an independent presence, so that, say, the “EU state” cannot amend its own primary law;

- supranational laws, institutions, and policies are an extension of the collective will of the Member States, meaning that they do not represent the interests of the Union at-large, as they are instead tasked with fleshing out the specifics of a compromise between competing national interests;

- the supranational level as seen from the perspective of a Member State, is in effect a theatre of international relations, which has certain peculiarities compared to more global issues, so that “Europe” and/or “Brussels” are always depicted or conceived as either an assertive bureaucracy or a highly specialised technocratic apparatus for extending the reach of a certain coalition of national interests.

The prevalence of inter-governmentalism

The right pillar on the illustration presents the Union’s Member States as supporting the entire edifice. Apart from nation states being the contracting parties, national governments are involved in every part of the political life of the EU.

Starting from the top, the heads of state or government congregate as European Council, whether in regular meetings or extraordinary ones, to engage in the process of formulating the Union’s political direction. I call this the exercise of rule formation.

The European Council is not the executive of the Union, in the sense that it does not deal with the particularities of administrating every area of policy that falls within the EU’s competences. It is best understood as the political strategist, the institution which provides the general direction and lays the parameters within which technical measures are established (hence, rule formation).

Rule making via the legislative procedure

The entity tasked with fleshing out those technicalities is the European Commission (hereinafter referred to as the Commission). This is the Union’s executive. In the 2014 European elections, a certain process took place by which the leading candidate of the winning group was to become president of the Commission. The German word for “leading candidates”, spitzenkandidaten, is often used to describe this process; one that has been lauded by parliamentarians as a bold step in the direction of making the Commission more democratic.

While there may be an intrinsic value in there being spitzenkandidaten, I very much doubt the function they perform in “democratising” the Union’s executive. The reason is two-fold:

- the European Council (not some European Demos) continues to be the institution which provides the Commission with its mandate, via the formation of rules;

- every Member State has their own Commissioner, suggesting that national governments are bargaining with one another to find a suitable compromise on the persons who will be appointed in office.

The Commission is the institution which initiates the rule making procedures. Though the practical details are not pertinent to this article, we may note the following:

- the Commission receives guidance from the European Council;

- based on the latter’s rule forming exercise, it creates legislative initiatives that are meant to render substantive that which the national leaders only agreed at a surface level;

- the proposal will typically fall within the ordinary legislative procedure, meaning that it will be sent to the two co-legislative institutions of the Union, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union;

- once Parliament and Council agree on a common final text, it becomes law of the Union.

The Council of the EU as an inter-state platform

As we are on the topic of inter-governmentalism and the importance of the right pillar in the illustration (EU Member States), attention should be given to the Council of the European Union. Unlike the European Council, it participates in the rule making process, dealing with the specifics of every piece of law. The Council’s peculiarities reflect two of the Union’s features:

- its inherent inter-state nature, since the Council is made up of ministers from national governments (so it is not like a Senate that has directly elected members);

- the understanding of “Brussels” or “Europe” as a special case of international relations, manifesting in the presence of each state’s Permanent Representation to the EU (embassy to the EU), and in the concomitant Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) inside the Council, whose role is, inter alia, to prepare the diplomatic aspects of a ministerial meeting.

EU Member States are thus involved in every step of the process, from forming the rules, to actually making them. The supranational stratum is, as Ar. 1 TEU stipulates, but an extension of the collective will of the Union’s contracting parties.

Further, demographics are the determinant for voting power in both the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. This is problematic, as it offers no means by which the good of the place may indeed be harmonised with the good of the space (the USA model, where the House of Representatives uses demographic criteria, while the Senate has a fixed number of senators for each state, is more successful at striking a balance of interests between competing states and the Union at-large).

Inter-governmentalism therefore becomes this political calculation of always trying to involve the bigger states, which may also furnish an explanation as to why the France-Germany alliance is vital for the European integration process (and also why any narrow focus on “German power” neglects the role of other powerful states in the Union).

[see: EU federalism and the German Question]

The limited scope of European citizenship

Insofar as the general structure of the EU is concerned, European citizenship has to be understood as substantively inferior to national citizenship. This is not to suggest that it is worthless or undesirable, but that it does not entail the normative powers a national citizenship does.

In the illustration, EU citizens only support the European Parliament. Theirs is not so much a pillar as it is a scaffold. European citizenship does not enable citizens to do the following:

- elect the Union’s executive; an executive that would be independent from any overseers and that would be directly accountable to them;

- provide a fully fledged democratic mandate to the European Parliament, since currently the Parliament cannot initiate legislation and, therefore, may not be the prime mover for repealing any effective piece of secondary law;

- elect a genuine senate, because the Council of the EU is not functioning as a federal parliament’s upper chamber, but as yet another platform for inter-state bargaining.

[see: On the limitations of the European Parliament]

It is lamentable that European citizenship is unfulfilled: it is a citizenship manqué.

Sovereignty mismatch

Why is inter-governmentalism a problem? Are not the Member States democratic in their own right? And, a fortiriori, is not the EU qua extension of the Member States also democratic?

These are the sort of questions that may be posed by a well-meaning yet misinformed pro-european who wants “more Europe” on just about every area of policy. The fact that Member States are republics in their own respect, does not mean that their combination and modes of interoperation thereof necessarily render democratic the supranational sphere.

There are at least three modal features in the composition of the EU distinguishing it from a genuine republic:

- its primary law has as its constitutional subject the Member States, which are not a unified whole but a collective of independent units, meaning that the EU is not a state but a league of states whose basic law—its “constitution”—is contingent on the collective will of those states;

- European law cannot be properly understood as independent from the legal orders of its Member States, but rather as an extension or addition to them, suggesting that the EU is not a fully realised and independent constitutional order wherein its own state functions (executive and legislative) could proceed to independently amend their primary law;

- the aggregation of national democracies cannot deliver a greater democracy because the virtuous cycle of legitimation and accountability remains confined to national borders, so that the body or institution qua body or institution within which Member States proceed with common agreements has no outright legitimation from a singular body of citizens nor is it directly accountable to such a demos of the system at-large.

[see: Res publica and European Democracy]

The specificities of the Union’s institutional order reflect a fundamental flaw in the architecture of the Union: a mismatch between popular sovereignty and state sovereignty. This manifests in EU authority for the full compass of the system that is not commensurate with accountability and legitimacy for the policy-making entities as such: the flip-side of “common rules without common politics”.

Put differently, we do not have a “European People” or a “European Demos” as the constitutional subject, nor is such a body politic expressed in fullness in any instance of EU politics, including the election of the European Parliament (due to its inherent limitations, especially on constitutional issues).

The EU is a quasi-confederation

This system is akin to a confederation, a league of states bound together by a supra-state level that pursues ends common to the states. The reason we cannot label this Union a confederation proper is because of the nature of European law: a set of inter-state covenants between nation states.

It would have been a confederation if it were founded on a codified corpus of primary law, a constitution, which would provide for a foundational dual sovereignty, of the people and the nation states, that would give rise to the composite sovereignty of the Union as such.

Though a proper confederation is preferable to a quasi-confederation, I would argue that it too suffers from a major flaw: that of reifying the legitimation functions as distinct sovereign entities. By “legitimation functions”, I mean the following:

- citizens perform the function of legitimising and holding accountable their respective state;

- citizens perform the function of legitimising and holding accountable the space wherein their state operates, the Union;

- these are performed by the same constitutional subject—the citizens—while the only reason the functions are two is due to citizens’ two-fold capacity as citizens of their respective state and citizens of the Union.

By joining their two capacities they provide the basis for the harmonisation of the interests between space (the Union) and place (the state, the locality). At no point are the states separate from their people and, most importantly, their authority—state sovereignty—cannot be qualified as legitimate or indeed sufficient in the absence of popular sovereignty.

What I consider democratic sovereignty has as its prerequisite the interplay between popular and state sovereignty. To that end, treating the legitimation functions as distinct sovereignties, entails a separation between people and state. But how can there be a republic without a people from whence the res publica comes and where it may be appreciated as such? I claim that it cannot, if said republic is rooted in democracy.

I think that composite states are best designed as federations, where these two functions manifest in the federal administration as well as the bicameral structure of the legislature, forming a unified sovereign whole:

- the citizens in their capacity as Union citizens elect their House of Representatives as well as the federal government;

- the citizens in their capacity as state citizens elect their senators, which form the Senate as a separate chamber within a single, federal, Congress.

For the time being, the European Union is an inter-state formation, appearing as a quasi-confederation. Judging from the direction of short-to-medium-term integration, its status will not be altered.

If we were to encapsulate the present essay in a single term, it would have to be inter-governmentalism. The suffix -ism denotes a certain mentality, an ideology of sorts: it is not just about decisions being made between governments, but rather that decisions should be made between governments.

Another term we could employ, at least when referring to the European Treaties is inter-statism (I don’t use internationalism due to its connotation as a leftist end—for that I anyway prefer cosmopolitanism).

We should distinguish state from government, since the former remains a contracting party of an international treaty, even if the latter undergoes change: this is in line with the principle of pacta sunt servanda (which is why a certain people cannot unilaterally vote against an international covenant, unless isolation and/or war are to be considered sensible options).

Whatever words we may use, we should try to express the fact that the EU is not a republic and, given its operations over a broad range of policies, it is anything but a typical democracy.