Constitutional subject and order

This post is archived. Opinions expressed herein may no longer represent my current views. Links, images and other media might not work as intended. Information may be out of date. For further questions contact me.

Contents:

- Introduction

- Constitutional subject

- State organisation

- The Federal shape

- Conclusion

Introduction

One of the people I follow on Twitter has posted this thoughtful tweet:

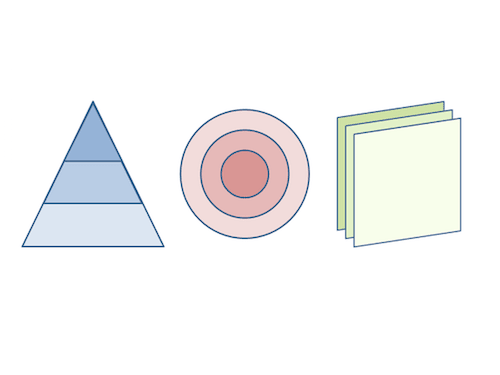

Which of the following shapes best describes the federal idea? Why?— Jakub Jermář (@jjermar) March 24, 2015

The present blog post is about some of the theoretical features of a constituted state, with occasional references to the case of the European Union. It is my attempt at an answer.

Constitutional subject

By “constitutional subject” we may refer to the primary entity of a polity, that is the ultimate formulator of the rules, norms, structures, institutions substantiating and underpinning the full array of relations that exist within it.

In a modern democracy, such is the citizenry. In the citizens rests the sovereignty of the state and from them stems the legitimacy of the government.

The representatives of citizens, democratic representation as such, albeit a central feature of modern democracy, is a technical/functional configuration, not a substantial one, for the representatives neither usurp nor substitute the citizens. They represent them, acting on their behalf within the confines of certain practical arrangements, without assuming their substantive constitutional status. If the body of representatives were to become constitutional subject in the citizenry’s stead, the system would transform into an oligarchy of some sort.

Democracy is an overarching qualitative theme that is distinct from the form of the state in which it applies. Profoundly different state formations can all qualify as “democracy”. Variations in form, or else the types of state organisation, are contingent on two factors: (1) the substantiation of the constitutional subject(s) in the channeling of sovereignty, and (2) the flow/direction of political action and its corresponding scope.

State organisation

In order to appreciate the notions of constitutional subject and political action in their application, let us proceed with an outline presentation of the three forms of state organisation closer to our immediate interest: unitary state, federation, confederation.

Unitary state

A unitary state has a single constitutional subject: the body of citizens. Political action proceeds in two directions, so that the citizens take the decision(s) that establish and maintain the governing order, while the government’s programmes eventually influence the lives of citizens.

If U is the unitary state, G its powers and C the body of citizens, then we have:

C → U

// sovereignty

U { G ⇆ C }

// political action

We claim that in a unitary state sovereignty is channeled directly from the body of citizens to the state. The constitutional subject is uniform and singular: the body of citizens. The constitutional object is the unitary state.

Within a unitary state, political action manifests as an immediate feedback loop between government and citizens.

Federation

A federation, features the citizens qua constitutional subject in two functions: (a) the body of citizens, and (b) the body of states, formed separately by the citizens of each subfederal state. Political action also flows in two directions, only it does so in separate phases.

If F is the federal state, G its powers, M the totality of subfederal states, C the body of citizens, E the citizens qua electorate of each subfederal state with A being the respective authorities and S the corresponding state, then we have the following:

C, M → F

// sovereignty

F { G ⇆ C, G ⇆ M, Sn ( En ⇆ An ) }

// political action

// the subscripts denote electorates, authorities for each subfederal state

In this case we have a more complex matrix of interrelations than that of the unitary state. The sovereignty of the federal state comes from both the body of citizens and the totality of subfederal states.

That C and M appear as separate entities is only a matter of nominal formulation. This kind of separation is meant to indicate the different functions the citizenry assumes. Note that the reason we postulate C, M → F instead of C → M → F, is to signify the equal footing C and M have with respect to F — the alternative would misrepresent M as an intermediary.

Seen from the perspective of an individual citizen, a federation has them perform a binary of roles as citizens of the federation and as citizens of their respective subfederal state. As I wrote on the same topic in my essay about Habermas’ European Democracy:

Those are not two distinct political-constitutional subjects, but a single subject — the citizens — in two different functions that pursue the same end: to bring together and to harmonise the good of the space with the good of the place. The resulting institutional heterarchy between Parliament and Council [in a bicameral system] is one of equality between functions.

In terms of political action, we witness the federation as a multifaceted assortment of feedback loops. The federal powers influence the body of citizens and vice-versa, the federation influences the totality of subfederal states and the other way round. Also, and encapsulated in S<sub>n</sub> ( E<sub>n</sub> ⇆ A<sub>n</sub> ), the individual states exhibit two-way relations between their authorities and their electorate.

To put it simply, a federation has a minimum of two levels of constitutional order at which sovereignty is realised. Both underpin the interweaving web of relations peculiar to political action.

Confederation

A confederation has at least three strata of constitutional order: (i) the body of citizens, (ii) the body of states, and (iii) the league/supra-state encompassing the member states. In this case, the scope of political action at the confederal level is predetermined. Member states opt to confer an exhaustive list of competences to the confederation. This makes them superior to the body of citizens in terms of constitutional agency, while it inserts an ex ante limitation on what the confederation’s objectives/powers are.

A confederation may consist of both unitary states and federations. While the above relations remain, there is the peculiarity of the supra-state level. A confederation appears to be very similar to a federation, so we will avoid reproducing the entirety of the previous formalisation, only focusing on the elements of differentiation.

If L is the [confederal] supra-state, G its powers, C the body of citizens, M the totality of member-states, E the citizens qua electorate of each member-state, U the unitary states, F the federal entities, and S the subfederal states, we get:

En → Un // unitary state

En, Sn → Fn // federation

M ⇉ L

// sovereignty

L { G ⇆ M }

// political action

// we use the two arrows (⇉) to signify the exhaustive list of competencies that are transferred from the totality of member-states to the confederation.

With regard to sovereignty, we notice a couple of important features: at first, each member-state has a more pronounced status than the subfederal states, typically to guarantee the preservation of its peculiar identity, which implies that the body of citizens cannot override the specific electorate over certain key issues (hence E<sub>n</sub> → U<sub>n</sub> and E<sub>n</sub>, S<sub>n</sub> → F<sub>n</sub> instead of C → M); secondly, the confederal level is granted specific competences by the totality of member-states with powerful constraints on its scope of action, also as a consequence of the elevated status of the member-states (and so we write M ⇉ L rather than C, M → L or even C → M → L).

The supra-state entity, the confederal level, is effectively a limited-purpose state of states.

Unlike a federation where a single constitutional subject performs multiple functions, a confederation has multiple constitutional subjects: apart from the totality of citizens, there exists the totality of member states. These have a hierarchy among them, which is made clear in the formation of the supra-state level, where it is primarily the totality of member states that substantiate its authority.

As for political action, and given the sovereign order of the confederation, the interplay is mostly between different states at varying levels. Even if the confederal level has a democratically legitimised government, it remains a state of states that decides for them and on their behalf on those areas of policy where they have permitted it to do so.

To recapitulate on the basics of this section, we have argued for the following:

- unitary states have a uniform constitutional subject;

- federations have a single constitutional subject in two different functions;

- confederations have multiple constitutional subjects;

- the functions of a federation’s constitutional subject are heterarchical;

- the constitutional subjects of confederations are hierarchical.

Just to be clear, all this is without prejudice to hybrid entities, which are permutations of these three types of state organisation. We also kept this examination limited to a skeleton version of a typical modern democracy.

The Federal shape

In light of the aforementioned, I would argue that the shape best portraying the federal idea is the third (the stack of squares).

The colour variation signifies the principle of subsidiarity, while the equality between the squares indicates the heterachy among the constitutional subject’s functions. None is above/below one another, none is closer to the “core”, the locus of authority, than any other.

What I have personally drawn from discussions with European federalists is that some of them would tend to argue for the triangle, as representative of the bottom-up multitude of decision-making levels. Others would opt for the circular one, as the concentric circles indicate subsidiarity.

If it were solely about decision-making, either version would be fine. Where both are found wanting is, I think, in the hierarchical arrangements they assume or tacitly suggest.

Conclusion

For any given constituted polity there exists a certain substantiation of the constitutional subject. In this article we have attempted to flesh out the notion of the constitutional subject and to use it as a criterion for the discernment of the main types of [modern democratic] state organisation.

Along those lines, we offered an outline presentation of the forms of unitary state, federation and confederation, each with the arrangements characteristic of them.

The gist is that a federation’s substantivist conception of the constitutional subject is of its functions as at once multiple and heterarchical. This is in contrast to a unitary state, whose constitutional subject is uniform and to a confederation where constitutional subjects are multiple yet hierarchical.

Predicated on such a claim, and in order to answer satisfactorily to the afore-embedded <a title=Jakub Jermář on Twitter href=https://twitter.com/jjermar/ target=_blank>@jjermar</a> tweet, the stack of squares is to be preferred as the shape best descriptive of the federal idea (or federalist ideal).

Given the arguments furnished herein, I might as well document my impression that the European Union, as it currently stands, is akin to a confederation — and a suboptimal one at that!

Thank you for reading!